|

|

|

Clark County Press, Neillsville, WI November 29, 1995, Page 28 Transcribed by Dolores (Mohr) Kenyon. Index of "Oldies" Articles

|

|

|

|

Clark County Press, Neillsville, WI November 29, 1995, Page 28 Transcribed by Dolores (Mohr) Kenyon. Index of "Oldies" Articles

|

Good Old Days

The Age of the Cast Iron Cookstove

By Dee Zimmerman

Home Comfort, Monarch, Kalamazoo, Novo, Majestic, and Alpine were some of the names cast in the nickel plated emblem on the Cookstove (oven door or warming oven).

Years ago, every country home’s kitchen had such a Cookstove or cooking range, it was a most essential necessity for the family’s livelihood. A Monarch graced our kitchen and I often thought that was an appropriate title, a bit of royalty that ruled our household.

Back in the 30’s, kitchens had similar furnishings – the big black Cookstove, wooden table with drop leaves, four or five wooden chairs (that didn’t match), large woodbox near the stove, dry sink with water pail, dipper and basin, and a Hoosier kitchen cabinet. A metal matchbox, (Christmas gift courtesy of the Creamery with its name stamped on) hung on a wall behind the stove. On another wall was a calendar with pockets, one for each month that held the bills and receipts, given by the local bank. Worn linoleum covered most of the floor and would wave up and down when a strong northwest wind crept under it from the gap between the back door and threshold.

The Cookstove had various accessories to maintain its operation. A long handled poker was used to move around chunks of wood in the firebox. Another tool cleaned soot out from a space above the oven and below the stove top which collected as smoke made its way to the chimney. A handled tool was used to remove the stove top lids.

A couple times a year, the Cookstove got a polishing, a black liquid like shoe polish was wiped over the cast iron, but not the cooking top. Mother would wad up waxed paper and brush across the hot lids, melting the wax, gave it a shine. The nickel, chrome trim was scrubbed with Bon-Ami and buffed until it sparkled.

Dad was the first one out of bed in the morning. He would start a fire in the Cookstove and space heater. He’d then fill the aluminum tea kettle to heat water, fill the coffee pot and after the kitchen warmed up he started calling, “time to get up.” We dreaded crawling out from under warm blankets in the unheated upstairs bedroom. No time was wasted once our feet hit the cold floor – we ran down the stairs, into the warm kitchen. We took turns standing in front of the cookstove to change into our school clothes. Care was taken not to bump our bare skin against the stove, a neighbor boy did and had serial numbers branded on his back side.

Mom prepared breakfast of cooked oatmeal or cream-of-wheat on school days, but on weekend mornings we were treated to homemade buttermilk or buckwheat pancakes prepared on the large cast-iron griddle set on the cook stove’s top. Sorghum syrup was set in the warming oven to be ready for serving over the hot pancakes. Beef stews, boiled dinners, and soups simmered on the back burners making palate pleasing meals on cold winter days.

Many loaves of bread, pans of rolls, cookies, cakes and pies were baked in the Monarch’s oven. The thermometer gauge visible on the oven door no long registered the temperature but mother seemed to know when the oven was ready for baking by the amount of wood and fire in the firebox. Sometimes she sprinkled water on the cooking top and the rate of evaporation indicated the stove’s heat.

When mom brought a chunk of dry yeast out that looked like glued sawdust and nearly as hard as cement that was put into a small bowl of warm water, then placed in the warming oven – the next day she should mix up and bake bread. Whenever she made loaves of bread, some dough was saved for a large pan of cinnamon rolls. As the rolls were put in the oven, a mixture of brown sugar, top-of-the-milk-can cream and vanilla was put into a pan set on back of the stove to melt and marinate. The caramel topping was poured over the hot cinnamon rolls five minutes before coming out of the oven. Visions of that sent us rushing home after school on bread baking days, we could each have one cinnamon roll before supper and as many as we wanted after supper. That cooking range oven baked bread to perfection – loaves with thick crust that crunched when a slice was bitten into.

On the right side of the oven was the water reservoir that held and heated water to be used for washing dishes, etc. One of my jobs was to hand pump water from the well near the house, carry it in and fill the reservoir at least twice a day. The wood box had to be filled once every day.

Baths were taken every Saturday night, each family member having a turn at bathing in the big galvanized tub set on the floor in front of the lowered cookstove oven door. An old blanket was draped over the backs of three wood chairs circling the tub to keep the warmth from escaping.

In preparations for washing clothes on Monday, a large copper boiler was placed on top of the stove and filled with water to be heated. The whites were boiled in the boiler after being washed in an attempt to bleach the cloth, especially shirts and blouses. Ironing clothes was done with flat irons that wee heated on the cookstove top. We had three flat irons that were interchanged to be able to continue the ironing process.

A length of clothes line rope was strung across behind the stove for wet dish towels, socks, snow pants, etc. to be hung on for drying. During the winter, wet mittens, gloves, boots and caps were laid on the floor circling the stove knowing all would be dry the next morning.

An elderly Norwegian friend, “Uncle Otto,” told how his parent’s cookstove served as an incubator to sustain his life as a premature baby. The doctor wrapped the tiny infant in some flannel cloth and laid him in a shoebox with soft material or cotton in the bottom, then set the box on the opened oven door. Heat from the cooking range oven provided the right amount of heat for the tiny babe. In other such cases, the water reservoir was emptied and the infant placed in there.

Living on a farm, our cookstove served as an incubator for our baby chicks. Each spring, we would get an order of at least one hundred chicks and mother would say, “Sure enough, the week those baby chicks from the hatchery arrive, it will be cold and rainy,” and it usually was cold weather. That meant a pen had to be made for the chicks in the corner behind the cookstove. Several layers of newspaper were put on the floor and ten inch wide leaves from the dining room table were propped around two sides to make an enclosure for the little peepers with hopes they could soon be put outdoors before their sprouting wing feathers enabled them to become airborne over the table leaves.

We were living in South Dakota when the Armistice Day storm of 1941 struck. My dad sensed the possibility of bad weather that morning so prepared. The horses, beef cows and hogs were put in the barn, fed and watered. The chickens were cared for and wood was carried into the house, the snow fall got heavier and the wind velocity increased, creating a “prairie white-out.”

The snow storm raged all day and night. The next morning, when the storm ended, dad went out to check on the poultry and animals. As he shoveled snow away from the chicken coop, he found a pheasant buried in the snow next to the door. Dad picked it up; it was alive but couldn’t move so he carried it to the house where mom placed it in a big cardboard box in front of the cookstove oven door. An oven rack was weighted down on the top. Returning outdoors, dad found six more pheasant buried in snow along the buildings where they had gone seeking shelter from the fierce wind and snow. By noon, the pheasants were moving around in the boxes and ready to be released in the farm yard where dad had scattered some grain for them. Later, we would occasionally hear a rooster pheasant crow in the field behind the buildings and I would wonder if it was one of those we had rescued.

When neighbors and friends came to visit in the winter, we always gathered in the kitchen. The grown-ups drank freshly made hot coffee and the kids were treated to hot cocoa with a big marshmallow floating on the top along with cookies. The heat from the cookstove added to the pleasant atmosphere that warmed the body and mellowed the soul.

The day that the old black Monarch was carried out of our kitchen was a day of mixed emotions, it was like losing a long time friend – there were memories not to be matched by the bottle gas range that took its place.

|

Mrs. Stafford, who owned and operated the Reddan House at 137 East 5th Street;

Meribah Stafford opened the boarding house in Neillsville after the death of her husband, Leonard. In 1873, she married James H. Reddan, thus the name Reddan House. (Photo courtesy of Clark county Jail Museum and thanks to Ruth Ebert, a Neillsville Historian)

|

Cash Hardware was located on the northeast corner of 5th and Hewett Street in the late 1800’s. Just as a customer entered the front door, the small model of a shiny new cooking range was on display. To the right, an assortment of cook stoves was lined up along the wall ready to be purchased. (Photo courtesy of Clark County Jail Museum)

|

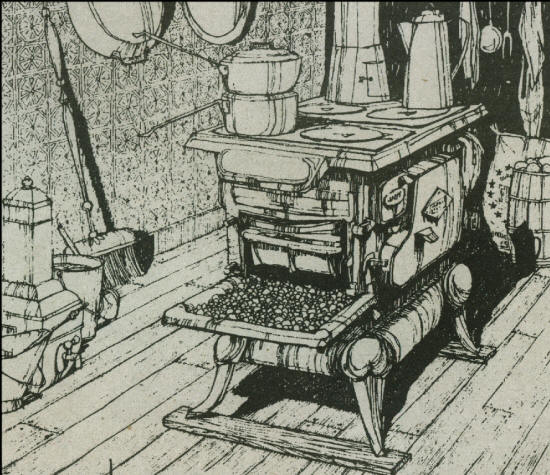

Soon we will hear the familiar words from a favorite Christmas song being sung … Chestnuts roasting by the open fire … this line of the lyrics was derived from the scene such as that above. This model of cooking stove had the extended cast iron shelf connected to the fire box that generated a large amount of heat along the iron plate, ideal for roasting nuts for the holiday season. The stove legs were set upon boards to raise it higher form the floor, a safety feature because of the great amount of heat that the stove was capable of producing. It was surrounded by common items used in that style of stove’s era. (Photo courtesy of Ruth Schultz)

(Transcriber’s note: I love this page, as it brought back so many fond memories of my days at home as a youngster and up until the time when I married. Thanks Dee!)

|

© Every submission is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.

Show your appreciation of this freely provided information by not copying it to any other site without our permission.

Become a Clark County History Buff

|

|

A site created and

maintained by the Clark County History Buffs

Webmasters: Leon Konieczny, Tanya Paschke, Janet & Stan Schwarze, James W. Sternitzky,

|