|

|

|

Clark County Press, Neillsville, March 14, 2007, Page 17 Transcribed by Dolores (Mohr) Kenyon. Index of "Oldies" Articles

Compiled and contributed by Dee Zimmerman

Clark County News |

|

|

|

Clark County Press, Neillsville, March 14, 2007, Page 17 Transcribed by Dolores (Mohr) Kenyon. Index of "Oldies" Articles

Compiled and contributed by Dee Zimmerman

Clark County News |

March 1937

History of Logging in Clark County

(Second in Series)

After the pine was located and purchased, much work had yet to be done before logging operations began.

Camps and logging roads had to be built. Clearing of timber was needed for grading to make stub roads. If the timber was back away from the Black River, on a tributary, the streams had to be cleared of brush and fallen trees or other obstacles, which would hinder the free floating of logs.

Flood dams also had to be constructed to raise a sufficient head of water to float the logs down to the main river.

About the first of September, a select crew of men were sent to the woods under the leadership of an experienced camp foreman.

First, there was the location of the campsite; this was selected with reference to its accessibility to the timber. As it was an advantage to occupy the same set of camps for more than one season, they were as centrally located as possible. Also the camps were placed on high ground, due to a possible early January thaw or the spring floods, and were near a creek for convenience to water.

Germs hadn’t been heard of in those days, so everyone drank creek water without any evil effects. Perhaps the bugs came later, who knows.

The camp buildings usually consisted of: a cook shanty, sleeping shanty, stables, blacksmith shop and in the larger camps, a small building for an office.

They were built of long, slim logs usually from 12 to 16 inches at the butt and 8 to 12 inches at the top. Spaces between the logs were chinked with three-cornered pieces of split logs, usually cut from 2 to 4 ft. in length, with any holes that remained, being plastered with wet clay.

The buildings were low, not over 6 ft. in height at the eaves and the roof usually was made of double thickness of inch-lumber. The very early camps, when lumber was unobtainable, were covered either with a shake roof or a trough roof. A shake was pine split thin, similar to shingles, about 30 inches in length and nailed shingle fashion on small logs or poles, the ends of which made the gable end of the building. The trough roof was made of hollow logs, split in halves, two troughs up, then one trough down. This made a watertight roof, providing there were no knotholes in the troughs. Then, when chinked around the eaves, along with a covering of snow on top of the whole roof, it made a more substantial and much warmer roof than one covered with shakes.

In the first camps, before lumber was obtainable, the floors were either of clay or puncheon, which was split logs with the split side up and smoothed with an adz.

The sleeping shanty was a long narrow building, the length usually depending upon the number of men in the camp. There were two tiers of bunks, one above the other, on each side of the shanty.

A board was nailed upon the projecting cross pieces of the lower tier of bunks forming a seat for the men; this seat was called the “deacon’s seat.” The shanty was heated by a huge box stove, which was set near the middle of the shanty. Poles were fastened overhead around the stove and upon those poles; the men hung their socks and mittens at night to dry. Dry pine and hardwood made a hot fire. There was so much heat that those who occupied the bunks nearest the stove nearly roasted the fore part of the night. Then, after the fire went down, they nearly froze before morning. The bunks were either filled with marsh hay or straw, with a blanket over the straw and usually two blankets for covers.

Few camps furnished pillows, but for the most part the men folded their clothes and used them for pillows. Not very soft bed, but the men were used to it and after a hard day’s work; they slept as well as people do today on the finest mattresses and springs.

The real boss of the lumber camp was the cook. His domain was the cook shanty, where he was an autocrat. A good cook was a necessity and he had to be an artist in his line to satisfy the men.

The men were not exacting as to knick-knacks but wanted wholesome food, well cooked and plenty of it.

In the early days, the food was very simple. The staple articles in its preparation were beans, salt pork, flour and syrup, not corn syrup put up in pails, but the old-fashioned cane syrup in fifty gallon barrels. They wanted plenty of corn meal, potatoes and rutabagas, when they could be had. As to fresh meat, deer were plentiful and with no game laws and consequently no game wardens; venison was a staple article of diet.

For sauce and pie, they had dried apples, and with these at hand, it was really astonishing the dishes that a camp cook could concoct from the simple ingredients furnished.

It has been said that in the first camps, the cooking was done over a fireplace. Even later, after stoves were in use, beans were baked, from choice, in a “Bean Hole.”

A hole was dug outside the camp, in the ground, before the ground became frozen in the fall. When beans were baked, that hole was filled with hardwood and maple wood, if it was available. The wood was set afire and reduced to coals, after which some of the coals were raked out, in readiness for the beans. The beans were properly seasoned with plenty of salt pork, a dash of syrup was added, and then was placed in a large iron kettle, well covered and put in the “bean hole,” on top of the hot coals. Some of the hot coals that had been raked out of the hole were then raked back into the hole to surround the kettle. A layer of dirt was thrown over the top and was left for four hours. Later, when the beans came out of the kettle hot with all the flavoring of pork and seasonings, there was no comparing them with beans cooked by any other method.

In later years, the camps furnished nearly everything in the way of food that is found in a first-class boarding house.

Also later, many of the camps became furnished with mattresses and springs on the bunks, in place of straw. The tin dishes, iron handled spoons, knives and forks used in the earlier camps, were replaced with crockery dishes and silver plated knives, forks and spoons.

A large camp had both a blacksmith and a wood butcher.

A wood butcher had to have a fair amount of knowledge about carpentry and also had to know some things about wood working that many carpenters today know nothing about. He had to be and (an) expert with a broad ax for many of the timbers that he used had to be hewed out of the log.

He also had to be an expert with an adz, or shin hoe as some of the wood butchers called it, to finish in smoothing up the work that he had done with the broad ax.

First, there were oxen to be shod. Anyone who may have had any experience with oxen knows that there is a whole box of dynamite packed in the hind foot of an ox. A different method had to be followed in shoeing oxen, other than that employed in shoeing horses. The wood butcher constructed a frame consisting of four uprights of hewed timber, six-by-six or larger mortised in sills placed about four feet apart, one way and three and one-half feet the other way. It was about five feet in height with cross pieces mortised in crossways at the top, on one side about three and one-half feet from the sills with a stationary five-inch pole mortised in the uprights. Into the uprights, holes were bored with an auger where poles were inserted to form a windlass. One end of a cowhide piece was attached to the windlass and the other to the stationary pole by means of a chain.

The ox was then led into the frame, the cowhide cradle passed under him; then the chains were wound up, raising the ox in the air, amid much struggling and brawling. Abut as soon as the oxen’s feet were off the ground, he was helpless. The oxen’s legs were then securely fastened. Then the shoes, eight in number, one for each division of the hoof, were nailed on. The shoes were made by the blacksmith to fit the foot and were calked on both heel and toe.

The logging sleighs were huge affairs with three-inch runners. A sleigh was seven to nine feet long with beams long enough so the sleighs were seven feet on the runner and correspondingly heavy. The logs were usually eight-by-nine feet long and on an ordinary snow road, that was a heavy load for a span of horses. But on an iced road, an average load for one team of horses was from 7,000 to 8,000 board feet measure. One team had been known to haul over 16,000 feet to the landing in one load.

Besides sleighs, the butcher had to build and repair other items. There were always oxen yokes, cant hook stocks, ax helves, whiffletrees and eveners to be made or repaired.

In a small logging camp, the blacksmith was sometimes the wood butcher also.

After the camps were built, there were logging roads to build. The man, who laid out the road, had to have some engineering knowledge so as to reach the landing in the shortest possible distance. He still had to take advantage of the lay of the land. The road to the landing had to be as downgrade as possible. The main road usually followed a creek and was cleared of timber from 20 to 25 feet in width. All of the trees in the track, in the path of the sleighs, had to be grubbed out by the roots. All knolls were leveled and holes filled as there could be no short curves owing to the length of the sleighs and the size of the loads. Many times, bridges had to be built across the meanderings of the streams, which the road followed and if there were soft spots or spring holes in the road, those had to be corduroyed.

When the landing was reached, the area on the banks had to be cleared and skids laid, in readiness for rolling the logs on later.

At short distances apart and along the road, holes were cut back in the timber about thirty feet wide and sixty feet in depth. Stumps had to be cut close to the ground, where the skid-ways were built. On those paths, the logs were skidded preparatory to being loaded on sleighs and hauled to the landing.

After the main road was completed, there were the side or branch roads that had to be built as well as skidding trails from the skidways, which went back into the timber.

The main road always followed the lowest ground. There was usually a ridgeback on each side of the road. These ran from a few rods to one-fourth mile or more to the top of the ridge. Branch roads were cut at convenient intervals, intersecting with the main road.

If the contour of the land permitted, a branch road was built around the end of the ridge, intersecting with the main road further down. Then the timber from the other side of the ridge was hauled out on that branch road.

A good camp foreman, in laying out the roads, as well as all of the other work, saw to it that every advantage was taken of the lay of the land. That enabled getting the logs on the skid-ways with the least expenditure of manpower and horse-power possible.

There were no labor unions in those days, no jobs of only 30 or 40-hours per week. The men were expected to do an honest day’s work for the wages they received and as one observer said, “One honest-to-goodness lumberjack accomplished more work in a day than the average worker does now in a week.”

The lumberjacks were through breakfast in the morning and in the woods as soon as the sawyer could see the log-mark on the fallen trees. This rule included all of the woods men.

The teamsters were out in many camps long before daylight and unless the haul was too long, they were at the landing by daylight.

It was necessary for the landing men to go out on the first load of logs, as the logs all had to be placed in rollways.

The workday lasted until the sawyers could no longer see a log mark in the evening. For the teamsters, skid-way men and the loaders worked much longer. Unless for some good reason the sleds were loaded at night to be ready for the teams and teamsters trip to the landing, the first thing in the morning. The skid-way men had to stay in the woods until the last team’s sled was loaded and set out for the night, ready to go in the morning.

The average wages paid was around $26 per month, with the exception of the teamsters who got from $30 to $35 per month. The taffler and cookee, who were usually a well-grown boy or an elderly man past the age of hard woods’ work, each received from $16 to $20 per month.

Like the men who owned the timber, many of the earlier lumberjacks came from Maine, New York State and Pennsylvania.

They were sturdy pioneers, descendents of immigrants who settled their native states and who for a large part had been connected with the lumber industry for generations.

As the timber began to become scarce in their home state, and hearing of the immense pine forests of central and northern Wisconsin, they came here to continue their work in the pine timber.

There were the homesteaders lured to Clark County in the 1860s, by the opportunity of acquiring cheap homes. They usually would settle on a few acres of a hardwood ridge, where they would roll up a log house to live in. Some of the men from those families worked in the logging camps during the winter. In the summer, they would return to their families and homesteads where they worked at clearing off a few acres of land. They would put the acres into either wheat or oats for a catch crop, then seeding it to grass seed for hay the following year. The money received for their winter’s work helped them to support their families and get them through the pioneering stage of developing a farm.

In the late 1860s and early 1870s, there was a large immigration from the different provinces of Germany, families coming to Clark County. These people also were looking for cheap lands and those men too, worked in the lumber camps.

(To be continued)

•••••••••••

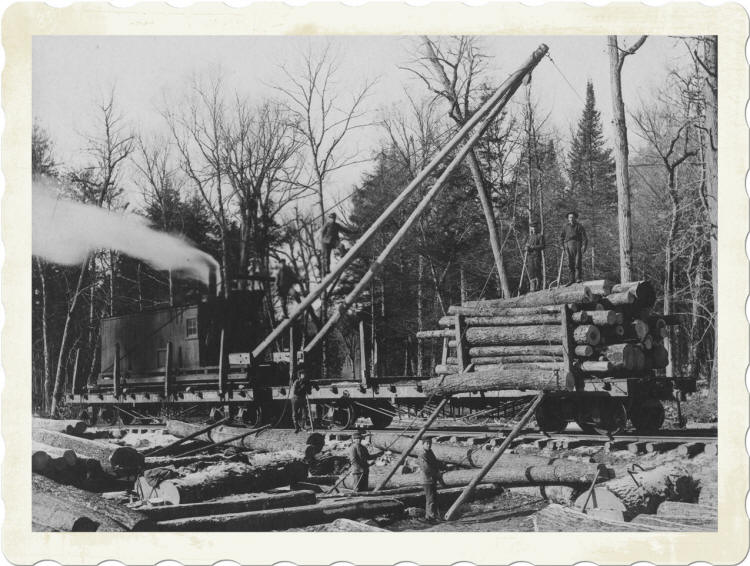

There is an old saying, “Where there is a will, there is a way.” That was very true in the early logging days. An apparatus was assembled using pine logs of the right sizes, log chains and lengths of rope, which along with the strength of a team of horses was able to roll logs upon sleds for transporting the logs. After the availability of railways, flat cars were loaded with logs to be hauled to saw mills by the same method.

¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤

|

© Every submission is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.

Show your appreciation of this freely provided information by not copying it to any other site without our permission.

Become a Clark County History Buff

|

|

A site created and

maintained by the Clark County History Buffs

Webmasters: Leon Konieczny, Tanya Paschke, Janet & Stan Schwarze, James W. Sternitzky,

|