|

|

|

Clark County Press, Neillsville, March 21, 2007, Page 11 Transcribed by Dolores (Mohr) Kenyon. Index of "Oldies" Articles

Compiled and contributed by Dee Zimmerman

Clark County News |

|

|

|

Clark County Press, Neillsville, March 21, 2007, Page 11 Transcribed by Dolores (Mohr) Kenyon. Index of "Oldies" Articles

Compiled and contributed by Dee Zimmerman

Clark County News |

March 1937

History of Logging in Clark County

(Third in a Series)

The experience of one of the immigrants, in the early 1870s, was typical of many others who came to Clark County at that time.

Quoting his words, in a conversation in 1886, and as near as could be remembered:

“I came to Clark county seven years ago, when I was about 33 years old, looking for work. Ever since I was old enough, I have worked. I succeeded in saving enough to buy a steerage ticket, for myself, to travel to America.

I got to Greenwood just before haying time and hired out to work for Jacob Huntzicker. I worked for him through the haying season at $1.50 per day, plus board, and thought I was getting rich. I made enough that haying season to send for my wife and three children, who arrived at that fall. I bought 80 acres of land, after making a small down payment. With the neighbors helping me, we rolled up some log buildings and I moved in that fall. Since then, I have cleared and seeded twenty acres, besides working in the woods during the winters.

D.J. Spaulding, who at one time was one of the largest loggers in Clark County, used to send to Norway for immigrants. Through the steamship immigration officials, he was able to get Norwegian lumbermen to work for him. He was able to send each man a ticket, through the steamship company. After each man arrived, he would work for Spaulding, paying for his passage to this country. As Spaulding was well liked by his men, they would return and work for him, winter after winter.

A story was told, in this connection of which we can’t vouch for, but is given for what it is worth.

Ole, who had some knowledge of English, visited Black River Falls, the home of Spaulding. While there, he wandered into a church as a revival meeting was being held.

After the sermon, as was the custom, an altar call was given. Several of those sitting near Ole, went forward, leaving him conspicuously alone. The minister walked down the aisle and addressed Ole as follows: “My friend, don’t you want to be saved?” Ole not understanding just what had been said, said nothing. The minister to make it more emphatic said “Don’t you want to be a Christian and work for the Lord Jesus Christ?” Ah! Here was something Ole could understand, “work,” so he replied, “Ay not tank I work for Jesus Christ. Ay work for Dudley Spaulding, sixteen dollars a month. Me no tank me jump me job.”

The winters were usually extremely cold. Unless the weather conditions were unusual, there was seldom a thaw that affected the logging roads before about the 20th of March. The standing timber kept the snow from drifting, keeping it a more uniform depth.

The cold weather made it necessary for the men to dress warmly and each lumberjack had a type of dress all his own. They were dressed mostly in mackinaws, which were made of heavy woolen goods. The shirt, jacket and trousers were usually alike. Each man wore a tall peaked hat to match, with the point thrown back over the head and it usually extended to the neck, having a tassel at the tip of the point.

Upon their feet; until about 1880 when rubbers and socks came into use, they wore for the most part, boot-packs. These were fashioned something like an Indian moccasin, but with a moderately high top. They were made of a very heavy cowhide, usually of a dark red color with no extra sole and very little heel. These were made large and roomy so as to hold plenty layers of wool socks. The men usually had either a sheepskin insole with the wool, or else put a layer of hay in the bottom.

After wearing these, a short time, the bottoms became as smooth as glass and unless care was exercised, the unlucky owner was likely to get many a fall.

To see a bunch of shanty boys, together, was a colorful sight. Their caps and mackinaws were nearly all the colors of the rainbow and some not to be found in a rainbow. Reds were the predominate color but there was always a sprinkling of blues, greens, whites and stripes, besides the variations.

In describing the camp equipment, one important thing was the wannigan. This item was usually kept in the camp office and it was the duty of either the scaler or the foreman to look after it and keep the books. The wannigan consisted of a supply of mackinaws, socks, mittens, boot packs and later rubbers. Also it had the different brands of smoking and chewing tobacco, both plug and fine cut, and a supply of the common medicines. A man was able (to) get whatever he wished. The cost was then charged to his account and taken out of his paycheck when he settled up at the end of the season, in the spring.

No liquor was allowed in the camp and for good reasons. Also in many of the logging camps, card playing was taboo.

After the camps and roads were built, the actual cutting of logs began. In the early days and until the late 1870s, only the very best of the timber was cut. The contracts, where the logs were sold to the mills or where the logs were put in on contract, called for an average of 2 ½ logs to the thousand feet for the season cut. No hollow logs were taken, no matter how small the hollow. The reason given was that in driving down the river, sand and gravel were apt to get in the hollow and injure the saws in cutting them into lumber. The logs also had to be free of punk knots, ring rot and shake. Consequently, there was an immense amount of timber left on the ground. Some of it was left to rot and much of it to be picked up later and sawed in the local mills.

Besides this waste, where the larger trees were cut out, it let the sun into the exposed roots of the standing trees. This, together with destructive fires started in the slashings, ruined thousands of acres and millions of feet of standing timber.

From the commencement of logging up to about 1880, the trees were all felled with an ax. Most of the hardwood and the last of the pine were cut down with a saw.

The ax man or chopper, as he was called, had to be a man of judgment as well as experienced in the use of an ax.

He must be able to judge the way a tree would fall and to the best advantage to be hauled to the skid way, butt first. The tree was fallen either directly away from the skid way, or else at right angles to the skid way. Care had to be exercised not to fall the tree across a stump or log, so that it wouldn’t break and spoil a log. Then too, at times the direction of the wind was blowing was a factor to be taken in consideration. A good chopper also judged the width of his scarf so he could fall the tree with the least amount of chopping possible, cutting the stump square across and the upper cut smooth enough to write on it with a pencil. (The scarf was a cut-away, or notches to be brought together so as to form a scarf joint in felling a tree. D.Z.)

The chopper was followed by the swamper. The swamper trimmed off the limbs, close to the log and threw those on one side of the log, far enough away so the skidding crew could easily skid out the logs. It was also his duty to do the measuring of the tree and mark it for the sawyers.

The sawyers followed, cutting the tree into logs. If the weather was mild, it was necessary for the sawyers to carry a bottle of kerosene with them. They would sprinkle kerosene on the saw, as the pitch in the sap would start running on a mild day and gum the saw.

The sawyers were followed by the skidding crew, which consisted of a yoke of oxen, the driver and a crotch tender. The crotch tender was usually a husky young fellow. He had to be able to pick up the crotch, with sometimes the added weight of snow and ice, and place it beside the log in readiness to roll the log on the bunk of the crotch.

The end of the chain, with the hook, was put over and under the log and hooked to the bunk of the crotch. The log was then rolled onto the bunk with the team, care taken to balance the log exactly in the middle of the bunk. Otherwise, the unlucky bull puncher very likely would have to reload the log before he reached the skid way. As soon as the log was balanced across the skids, it was rolled in place. If it was a small log, very likely it was rolled on top of the other logs by means of cant-hooks and spiked skids, which bit into the bark and prevented the log from slipping.

Sometimes a log was so large that the team was unable to haul it to the skid way, as it was. The log was then peeled of its bark, about one-half the way from the top to the butt and one-third the way around. This greatly lessened the resistance and one team was then usually able to haul it.

Snow usually fell in quantities sometime about January first, to the tenth. The ground ordinarily was frozen hard before the snow fell. If there were still soft places on the marshes, or spring holes, men were sent out to tramp a track for the horses to follow. After the track was tramped, the frost went down and the next day, these spots were usually frozen hard enough to hold up the horses. A huge snow plow was made of three or four inch planks, about 16 or 18 inches in height and 20 to 24 feet in length, well braced and V-shaped with an 18 or 20 foot spread. The plow was drawn the length of the logging road, throwing back most of the snow. Then four horses were hitched to a logging sleigh with a gouger, or rudder behind, which followed exactly in the sleigh tracks. This apparatus was made of wood with heavy steel blades 4 to 5 inches in width, set at about the same angle as the blades in a carpenters’ plane. At the back end was fastened a set of handles, similar to those on a breaking plow, of the purpose of keeping the gouger in an upright position and also to steady it. This gouged a rut, from three to five inches in depth, in the frozen soil. It was necessary for men to follow it, digging up any small stones that might be in the rut. They had to take out any other obstructions that would interfere with the free flow of water in the rut trench.

The road was then left until the entire road was frozen solid. Then began the task of filling the ruts with water; an immense wooden tank was filled water, after it was placed upon sleighs made especially for that purpose. The runners curved at both ends so that when the tank was emptied of water, instead of having to turn around, they unhooked the horses and fastened them to the other end of the sleigh, for the return trip. In the old days, the water was hauled and dumped through a trap door in the top of the tank. The tank was filled by the means of a good sized barrel equipped with a heavy bale, pulling water from the river. The barrel had been placed on a pair of skids and was hauled by a team of horses, making trips back and forth to fill the tank. In later years, the tank was filled with a gasoline pump and a five-inch hose, in a small fraction of the time it took to fill the tank the old way. After the road ruts were completely iced, it was ready for hauling logs to commerce (commence). Following the first icing, the water tank was run nights, to re-ice the ruts, when the road was free from traffic.

A practice up until sometime in the late 1870s, the log loads were built to a peak, bound with chains and a binding pole. This wasn’t a very satisfactory method as the binding pole sometimes worked loose and accidents occurred. Then some-one discovered corner binds, which securely held the outside logs so that it was impossible for the bottom tier of logs to slide out, as some did, (with) the old fashioned method. Then, too, the sides of the load could be built up almost perpendicular, which was a decided advantage.

After reaching the landing, the logs were unloaded by the landing crew and if the landing was small, the logs were sometimes decked high with a decking chain and team.

The usual procedure was to have landing space enough so that the landing crew could roll them up by hand with the aid of spiked skids. The bed of the creek, or river and the ice on the flood dam was also made use of as a landing.

The logs were all side marked by the landing men. They would cut the owners mark through the bark and into the timber, on the side of the log about equal distance from the ends.

All kinds of marks were used. Sometimes initials of the owners were used, such as C.L.C., which was the C. L. Coleman Lumber Company. Of course, the lumberjack’s interpretation of these letters, which Coleman’s also used on their harnesses and camp kit, could be different. The logging boys declared that the letters stood for Coleman’s Lousey Crew.

Hewett and Woods used H.W. as their mark. Sometimes they had a large mark cut into the bark with three smaller ones extending diagonally, right to left from the large notch. When they used this mark for a side mark, they used a barrel S for an end mark that looked very much like a $ sign.

The Crosby Lumber Company used a letter V, with another V bottom side up, which crossed the first V.

Another mark was XIX, which was believed to have been that of Robert Schofield. When all the logs from the tributaries got into the main river, below the mouth of the East Fork, there were hundreds of different marks. Each logger or contractor had his own particular mark.

After the logs were in the rollway and marked with the side mark, the logs were scaled by the scaler who used a Scribner log rule. As the logs were scaled, he stamped the logs with an end mark, which was usually the same as the side mark. The stamp was a cast iron hammer, or design cast in the end and weighed in the neighborhood of three pounds.

After the spring break-up came, there were usually two or three weeks before the ice broke up sufficiently in the streams for the log drive to start. The gates to the dams were closed to keep a head water. The loggers always hoped that the break-up would come with a rain, but sometimes the snow went away gradually and the early April rains failed to come in sufficient quantity. When that happened, most of the logs were left high and dry on the banks and sand bars before they reached La Crosse. Then there was nothing to do but wait for the June rains.

(Continued next week)

•••••••••

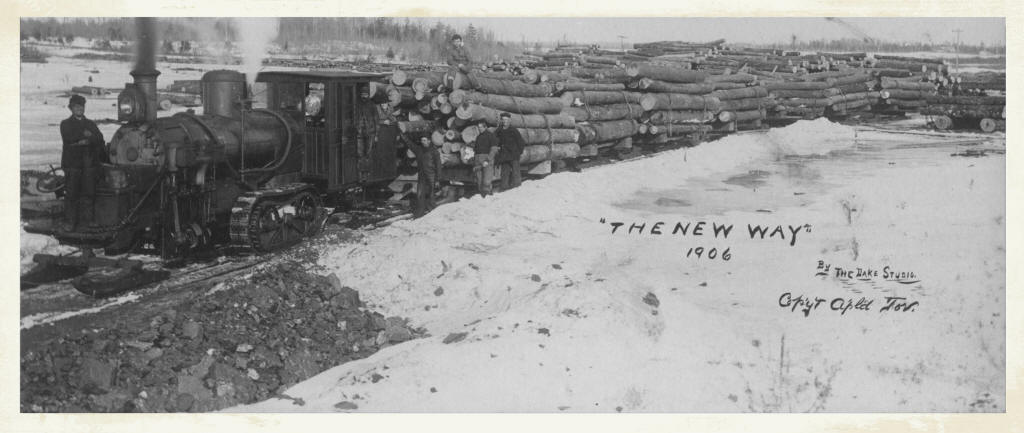

By the early 1900s, as this 1906 photo indicates, taking logs from the woods had taken on a new method. In this operation, a railroad engine was equipped with a set of tracks, one each side, and a set of sled skis on the front, which was able to pull several sleigh loads of logs across the snow, in one trip.

¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤

|

© Every submission is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.

Show your appreciation of this freely provided information by not copying it to any other site without our permission.

Become a Clark County History Buff

|

|

A site created and

maintained by the Clark County History Buffs

Webmasters: Leon Konieczny, Tanya Paschke, Janet & Stan Schwarze, James W. Sternitzky,

|